To meet the demand, new generation capacity is being added worldwide. However, in many grids, growth of non-programmable renewable generation is outpacing flexible and firm electricity sources. Long-duration energy storage (LDES) is therefore essential to balance the supply and demand of electricity.

Lithium ion batteries and long duration energy storage

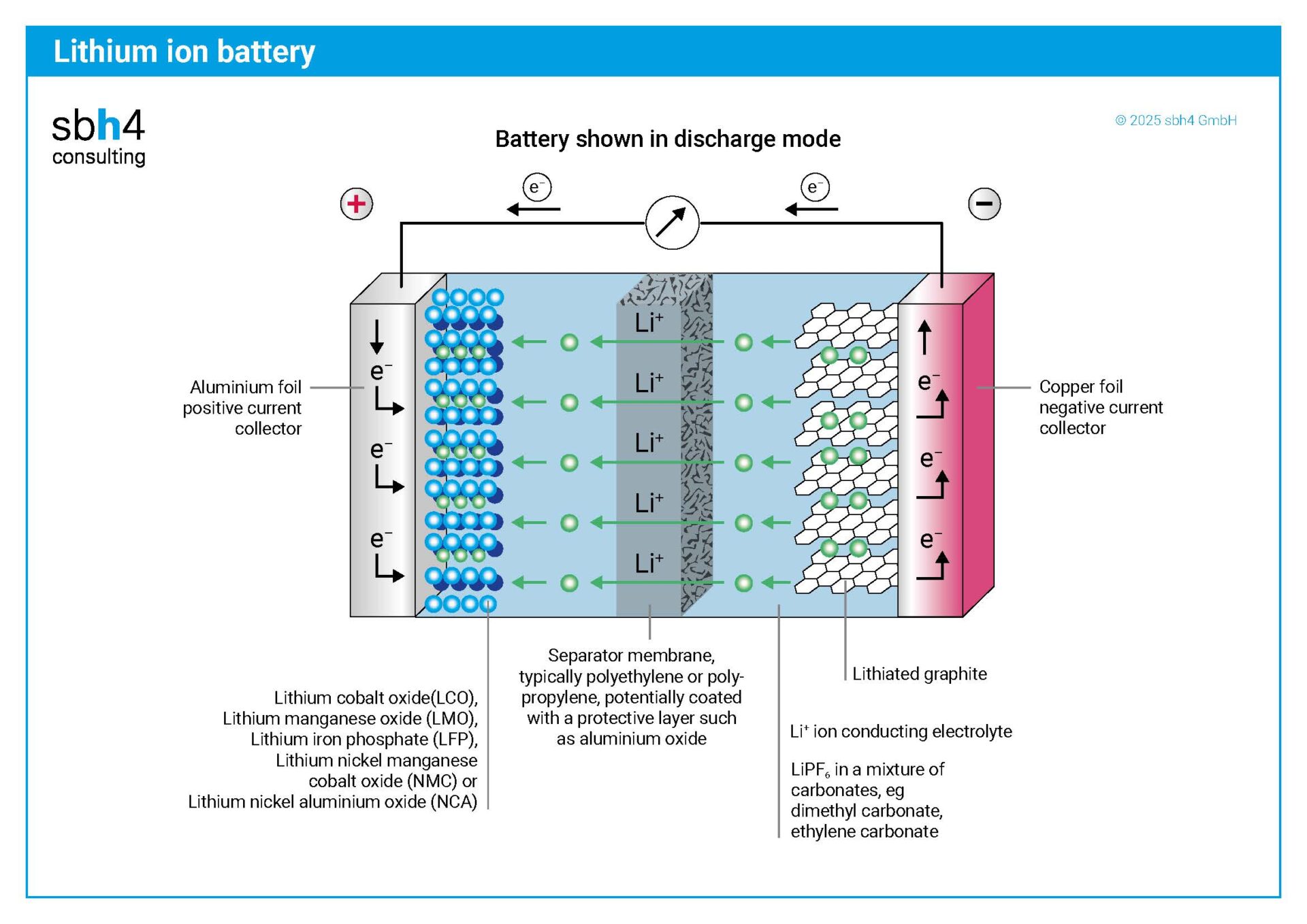

For daily balancing with a discharge period of up to 4 hours, lithium ion batteries (LIBs) are unquestionably state of the art. LIBs are also the technology of choice for battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and handheld devices such as mobile phones and tablet computers.

Huge utility-scale LDES facilities are being implemented in many countries. They are typically able to supply 100 to 500 MW of power and store up to 2,000 MWh of energy.

For grid balancing, as is the major application in Europe, the discharge period of an LIB LDES scheme is generally optimised at 4 hours. For solar power time shifting in locations such as California, they must work overnight and typically discharge over an 8 to 12 hour period.

LIBs are complex electrochemical devices. At the end of life, valuable industrial metals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese are recovered during LIB recycling using hydrometallurgy and CO2.

Recycled CO2 for LIB electrolyte solvents

During charging and discharging electrons flow from the anode and cathode, and vice versa, through an electrolyte which is supported in a carbonate solvent which is produced using carbon dioxide (CO2).

The electrolyte is supported in a hydrocarbon solvent such as dimethyl carbonate (DMC) or ethylene carbonate (EC).

EC is produced by reacting ethylene oxide (EO) with CO2. For every tonne of EC, 500 kg of CO2 are required. CO2 for EC is captured and recycled from the EO manufacturing process.

DMC has traditionally been produced from the poisonous gas phosgene. The modern process for DMC production avoids phosgene and is therefore much safer. It reacts CO2 (which again is captured and recycled from the EO plant) with MC and thereby also enables synergy within an integrated ethylene derivatives chemicals complex.

Low-cost circular CO2

In March of 2024, Dow announced their intent to invest in a new ethylene derivatives plant on the U.S. Gulf Coast. This will produce carbonate solvents which are used to support the electrolyte in LIBs and will support growth in BEV and LDES markets.

As part of Dow’s Decarbonize & Grow strategy, the ethylene derivatives facility will capture more than 90% of the CO2 from Dow’s existing ethylene oxide manufacturing process. This CO2 will be utilised to produce the carbonate solvents.

CO2 must be captured during ethylene oxide production to enable process operation, making this one of the lowest cost sources of CO2. Utilisation of the CO2 prevents its direct emission to the atmosphere.

Strategic and critical material recycling

There are many types of LIBs, each with different active materials in the LIB anode. The highest energy density is achieved with Nickel, Manganese, Cobalt (NMC) LIBs. These are favoured in premium automotive applications and are displacing Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO) LIBs in premium mobile phones to extend their battery life.

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) LIBs are known for their low cost and are regarded as being safer than NMC LIBs. They are heavier than NMC batteries, but for static power storage applications this weight penalty is of no consequence.

NMC and LCO LIBs contain large amounts of cobalt, manganese and nickel. In the EU cobalt and manganese are both recognised as both strategic and critical materials. Nickel is regarded as strategic. Recovery of these metals during LIB recycling is therefore of paramount importance.

Reflecting these points, the EU Battery Regulation (2023/1542) is now in force. It is a very stringent framework for battery life-cycle management.

In 2026, at least 65% of the total mass of an LIB must be recycled. That requirement rises to 70% in 2030. Zooming into cobalt and nickel, the reprocessing recovery at the end of 2027 must be at least 90%. By the end of 2031, that increases to 95%.

To extract nickel and cobalt, it is necessary to separate them from lithium in the LIB.

Hydrometallurgical Lithium recycling

The initial stages of LIB recycling are brutally mechanical. The batteries are shredded to release the electrolyte and its solvent. Copper and aluminium foils are shredded and separated using air blowers. The resulting powder, called black mass, is a mixture of anode and cathode materials. It is rich in metal oxides, lithium and graphite.

Pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical techniques can be used to recover valuable critical materials from the black mass.

EU Battery Regulation currently requires 50% of the lithium to be recovered. This is aligned to smelting or pyrometallurgical recovery of LIB materials. However, this lithium recovery rate jumps to 80% for 2032 and beyond. This increase will force the industry to implement chemical-based hydrometallurgical recycling which is more efficient at recovering lithium from LIBs.

Hydrometallurgical recycling mixes the black mass with acids and alkalis. In the best processes, the metal oxides, lithium and graphite are all recovered to a large extent.

One pathway is to separate the hydrophobic graphite from the black mass in a similar way to natural graphite is separated using flotation baths after it has been mined.

To acidify the broth, CO2 gas can be sparged into the liquor. The dissolved CO2 converts lithium ions to soluble lithium hydrogen carbonate. This liquor can then be evaporated to precipitate lithium carbonate which is then captured as a cake using filtration.

Graphite recovery and reprocessing

At present, graphite is the mainstay anode material in LIBs. It is either mined from natural sources or produced from hydrocarbons such as crude oil.

There are many grades of industrial graphite. One of the key properties that differentiates each grade is the size and shape of the particles. Natural graphite is very flaky, composed of flat thin shapes. For LIBs, the graphite particles should be tiny, smooth round balls. This increases the packing density in the LIB and improves its electrochemical properties.

During hydrometallurgical recovery for recycling, the graphite particles may become damaged and lose their spherical shape. Additional processing is required to increase the quality and value of the recycled graphite particles to battery grade material.

Avoiding obsolescence

As with any emerging technology, in the field of LDES and batteries, there is rapid innovation which leads to product substitution and obsolescence.

NMC batteries are being challenged by LFP. The economics and process for LFP battery recycling are very different to NMC LIBs. If NMC batteries are no longer used, the recycling equipment may need to be modified and re-purposed for other battery technologies. Or, in the worst case, it may become redundant.

For stationary LDES, VRFBs and iron-air batteries are challenging the dominance of LIBs. In EV mobility, solid state lithium ion and sodium ion batteries are potentially safer and more economical options. If these newer technologies dominate, for LIBs may peak 15 to 20 years from now, plateau and then progressively decline.

The case for prudent investment

In the short- to mid-term, investing in LIB recycling would seem to be an extremely good bet on the clean energy transition. It would leverage a growing LDES market for stationary and mobile applications.

However, working with cyclical technologies complicates recycling investment planning. As innovation races ahead and substitute technologies establish, it will be essential to avoid over-capacity in a declining market.

Despite the technology cycles, prudent investments to support sustainable LDES will undoubtedly be possible.