During a full-day BIR workshop dedicated to India’s recycling potential, Dr Singh confirmed the country’s steel production capacity is to increase to 300 million tonnes by 2030. ‘Recycling can play a significant role in achieving this target,’ he told delegates. And he also revealed that the country’s first car shredder is expected to start operation by the end of 2018; a government-initiated joint venture will set up both this facility and a network of collection and dismantling centres in the greater Delhi region.

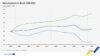

The initiative is one of the outcomes of a major economic and environmental transformation under the leadership of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who had endorsed the BIR World Recycling Convention in a written personal message. Boosted by a rapidly-expanding middle class, India’s GDP is expected to grow to around US$ 7 trillion by 2028 from US$ 2.3 trillion at present. The latest GDP forecasts (Oxford Economics, August 2017) for 30 Asian cities predict that those in India are set to grow the most; indeed, Delhi is expected to be the fastest-growing city in Asia over the next five years.

‘India continues to offer huge potential for growth due to major infrastructural development over the next 10-15 years,’ stressed BIR President Ranjit Singh Baxi in his opening address to the world recycling organisation’s first-ever convention in India. ‘This is the start of strengthening our bond of partnership and friendship between the global members of BIR that have joined this convention, with over 200 Indian companies present.’

According to Mr Baxi, India today is ‘at the forefront of growth and soon to be the second largest steel producer in the world’, clearly offering major opportunities for the country’s metal recycling sector.

Metal recycling in India offers ‘a huge untapped potential’, agreed B.B. Singh, Managing Director of Indian scrap trading company MSTC. He estimated India’s current recycling rate to be 20-25%. ‘By the year 2020, domestic scrap generation in India will reach 43 million tonnes, whereas demand would be around 53 million tonnes – a deficit of 10 million tonnes that needs to be imported,’ he stressed.

According to Mr Singh, ‘some hundred’ shredder plants will be needed to handle India’s growing domestic scrap volumes. ‘In the far future, once you have this capacity, India would no longer depend so much on imports of scrap,’ he said. ‘However, given this lack of recycling capacity and infrastructure, imports of scrap remain crucial over the coming years in order to feed growing scrap demand.’

Mr Singh sees huge opportunities for automotive recycling in India, boosted both by rapidly-growing car sales and the rising number of end-of-life vehicles (ELVs) becoming available. ‘The potential scrap generation from ELVs can contribute 10% of the total domestic scrap market,’ he said, adding that the first car shredder to be installed next year would be a major step in that direction.

At the same time, however, India’s recycling industry is facing major challenges such as a 2.5% metal scrap import tax as well as complex legislation and regulation which continue to frustrate day-to-day business operations for recyclers and traders both within and outside of India, such as through delaying container loads of scrap at the country’s main sea ports.

In her presentation, Dr Aruna Sharma, Secretary of the Ministry of Steel, hinted at the strong possibility that the government will do its best to temporarily lift, or at least reduce, the scrap import tax.

In his presentation, BIR’s Director General Arnaud Brunet called for better regulation. His message: keep it simple and workable. ‘Legislation is not an end to itself: it is a means to deliver tangible benefits and address common challenges,’ he stated. Furthermore, he called for: ‘fair enforcement against companies that are under the radar, rather than repeated checks on the largest and most compliant’; and for promotion, implementation and enforcement of multi-lateral agreements by, among others, the World Trade Organization and the United Nations.

Another challenge is presented by what is often described as the ‘informal sector’. New Delhi alone is home to some 100,000 waste-pickers while many millions of these informal workers find a living from scrap across India, often working in unhealthy and dangerous conditions. ‘We see waste mountains collapse and kids die, and we just need to change this,’ said KPMG consultant Dr Jaijit Bhattacharya.

Rita Roy Choudhury, Assistant Secretary at the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, believes the informal sector ‘needs to be integrated in the formal sector and helped to build better life opportunities’.