In the report “Toward a Circular Economy for the Electronics Sector in Central and Eastern Europe”, the project “Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM)” aims to show how a circular

economy for EEE can also be established in these countries.

High-income countries have an established infrastructure and the knowledge to manage e-waste. In low- and middle-income countries, on the other hand, the consumption of electrical and electronic equipment has grown rapidly recently, but the infrastructure is either still in its infancy or non-existent. The study therefore focuses on four countries in Central and Eastern Europe: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Georgia, and Moldova.

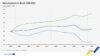

Bulgaria has the second-highest GDP per capita of the countries in focus. However, it ranks last among EU member states, with 55 per cent of the average GDP per capita. Over the past three decades, the country has moved from a centralised and planned economy to an open, market-based economy. The report notes that Bulgaria has strong traditions in electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, mechatronics and automation. The Ministry of Environment and Water (MOEW) is responsible for waste management. It is responsible for transposing EU legislation into national law. At national level, there are 16 regional authorities. The report also states that the country has had a strategy and action plan for the transition to a circular economy since 2012, which includes e-waste. However, the separate collection of e-waste has to be implemented with producers and importers. The latter have set up seven organisations to fulfil their obligations. The relevant EU regulation on e-waste is currently being transposed into national legislation. In 2017, 7.7 kg of e-waste per inhabitant were collected. This amount met the collection targets. However, the report explains that the amount of electrical and electronic equipment put on the market is underestimated. In addition, quantities are not always adequately reported due to treatment by the informal sector. Bulgaria‘s recycling rate is 2.3 per cent (2019), one of the lowest in the EU. The country also ranks last in the EU in the eco-innovation index. This is therefore an issue that needs to be addressed in the future.

Beyond the mandatory provisions of the Ecodesign Directive, the country has no specific policy focusing on circular design strategies. The production of WEEE accounts for only five per cent of the value added by the manufacturing sector in Bulgaria. The main products are electric motors, generators, transformers and electrical distribution equipment, batteries, wires and cables, lamps and lighting products. The amount of electrical and electronic equipment placed on the market in 2017 was 75.8 kt (10.6 kg per capita). The vast majority of these (72 per cent) were large household appliances. The report further states that Bulgarians are still mainly motivated by price when making purchasing decisions. There is also a lack of knowledge about efficiency and eco labels. As a result, the market for environmentally friendly products is underdeveloped. However, it is also noted that the country has a long tradition of repairing products. Consumers are still willing to repair their damaged goods if the cost is lower than buying a new product. Bulgaria has an e-waste collection rate of 66 per cent. The high collection rate is attributed to regular household collection campaigns. However, it is also assumed that some e-waste collected from businesses and institutions is reported as collected from households. There are several e-waste treatment companies in the country, which need a permit from the MOEW and local authorities. In 2018, the recycling rate was 66.7 per cent, much higher than the EU average of 41.2 per cent.

The report suggests a better dialogue between science and industry, which has been rather weak so far. There is also a need to better inform consumers to motivate them to buy more sustainable electrical and electronic equipment. The market for repair and refurbishment services also needs to be stimulated. The database needs to be improved. It is recommended that the government should not only rely on data from collection schemes and waste management companies. Certification of EoL operators in accordance with the EN 50625 standard is also recommended. With a GDP of USD 22,943 per capita, the Czech Republic is now considered a high-income country. EEE production is dominated by large international producers. The Ministry of the Environment (MoE) is responsible for waste management. There are also regional authorities. The Czech Republic transposed the WEEE Directive into national law in 2005. “The country has a well-functioning e-waste collection system with a dense network of collection points at municipal level and services provided to consumers, which enabled the country to achieve a collection rate of 57 per cent of the e-waste generated in 2018,” the report says. The country‘s recycling rate is 8.3 per cent below the EU average. In terms of eco-innovation performance, the country ranks 15th. In 2018, 196.9 kt of electrical and electronic equipment was placed on the market, equivalent to 18.6 kg per capita. As in many other countries, repair activities have declined – mainly due to the amount of cheap new products on the market. However, there are some initiatives. The amount of e-waste generated in 2018 was 164.00 kt (15.5 kg per capita). The collection rate in the same year was 57 per cent, below the current EU target of 65 per cent. The recycling rate was 43.6 per cent. The country has treatment facilities for most categories of e-waste. As mentioned in the report, there are challenges related to the increasing volumes of e-waste and rising labour costs. In addition, there is no market for recycled plastic parts from WEEE.

EPR for WEEE has been well established in the Czech Republic since 2005. According to the report, PROs are mandatory. The national WEEE Directive provides for the free take-back of WEEE. Awareness-raising activities are also part of the PROs‘ obligations. Producers must finance the collection, transport, handling, treatment and disposal of separately collected WEEE. PROs collect fees from producers, which are refinanced by consumers when they purchase electrical and electronic equipment. “Since 2021, it has been mandatory in the Czech Republic to make this fee transparent for customers as a ‘visible fee’ at the time of purchase.” There are five PROs that can collect all categories of WEEE. Other PROs focus on certain categories only.

The report suggests that the Czech Republic could initiate or support ecodesign initiatives and implement ecodesign requirements.

It also recommends the introduction of tax incentives for repair shops and the removal of legal barriers to reuse. The study also points out that stricter regulations for the transport and handling of equipment could be helpful.

Georgia, with a population of 3.7 million, has a GDP per capita of USD 5,016. The country has little local production of electrical and electronic equipment, the majority is imported from European countries. The Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture is responsible for waste management. The report states that the country has a well-established legal framework for waste. Georgia has ratified an Association Agreement with the EU, which requires the harmonisation of national legislation with the Waste Management Directive and the Landfill Directive. In 2020, an EPR system was applied to specific waste streams, including waste electronic batteries and accumulators.

The country generated 25.5 kt of e-waste in 2018 (6.9 kg per capita). However, there is no infrastructure for e-waste collection, so most of the waste ends up in landfills. On the other hand, reuse and repair are common practices in Georgia because the costs are low.

As Moldova is not a member of the EU, there is no data available on the country‘s eco-innovation performance and material use rate. Eco-design principles are not part of the national legal framework or private initiatives. In 2018, 40.5 kt of electrical and electronic equipment were placed on the market (10.9 kg per capita).

The collection of e-waste is the responsibility of municipalities. Companies must have a waste management plan and work with companies that have a treatment licence. “For the collection of e-waste generated by companies, the situation appears to be better than for e-waste from private households where, because of the very limited awareness of the population, little or no separation of e-waste occurs,” the report points out. E-waste is mainly handled by the informal sector. There is also no infrastructure for the final treatment of e-waste.

It suggests that the government establish and enforce the legal basis for sound e-waste management and eco-design principles. Other recommendations include incentives for repair and reuse, adequate infrastructure for collection, repair and recycling, and support for the establishment of local pre-treatment companies. There is also a need for consumer awareness campaigns. The population of Moldova was 2.63 million in 2020. The GDP per capita was USD 4,523. Most of the country‘s electrical and electronic equipment is imported. However, there are a few international companies in the country. In 2019, 30.3 kt were placed on the market. However, there are no statistics on e-waste generation. In theory, PROs should organise, manage and coordinate the separate collection of e-waste from private households. However, the infrastructure is not sufficient and there are no official operators for the pre-treatment of e-waste. The report notes that by legally requiring producers to register with the country‘s EPR and setting collection targets, the country has made significant progress towards the sound financing of e-waste management and treatment. The report suggests that the country should adopt legislation such as the EU‘s Ecodesign Directive. The country should also try to maintain its repair culture and encourage formalised and authorised repair services. There is also a need to develop a sound e-waste management system. It should consider whether it makes sense to continue exporting collected e-waste or to establish a national technical infrastructure.

[…] Source link […]